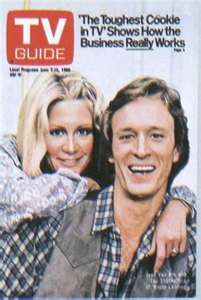

She looks you in the eye. Her best no-nonsense, I am-woman look. “I’m addicted,” says Joan Van Ark. “I need to run 10 miles a day. If I don’t, I feel cheated.”

The actress, one of the stars of Knots Landing, a CBS series about sedentary folk in California suburbia, sighs. “Running is my survival kit,” she says, with a loss of her elegant golden head. “You can’t cop out, you can’t fake it. If you run well, you forget that your lungs are bursting, your legs are killing you and you can’t go another step. All you know if you made it. You get a gold star no matter what.”

When she says she runs, she isn’t just whistling “Dixie.” She’s done the tough stuff. “I ran the Boston Marathon in 1979,” she is saying casually. “To qualify, you have to have run 26 miles in less than three and a half hours. So I entered the Mission Bay [marathon] in San Diego. It was raining and cold. I ran it with a 102-degree fever. I took two Tetracy Cline’s, one at a the 7-mile point, one at the 21. I made it, just barely.

“So there I am in Boston. I’m dying coming up Heartbreak Hill and there’s this Irish cop at the top. He smiles this beautiful smile and says, ‘All the rest is downhill, girlie’ They were the most beautiful words I’d ever heard in my life.”

This is a familiar little set piece Van Ark does to explain who she is. If she has said it once, she has said it a hundred times. Two things strike you about it: first, how removed the real woman is from the dependent housewife she plays in Knots Landing and, second, how far actresses have come since the days of automobiles with diamond wheels and the matched set of Russian wolfhounds.

She may be of the best young actresses around, yet she is in constant need of moral and psychological gold stars, obsessed with the idea that what she does is not good enough. It was never good enough that she should set her home town of Boulder, Colo., on its ear by playing Anne Frank at the age of 15 and go on to similar lead parts at the Yale School of Drama, the Guthrie Theatre in Minniapolis and the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., all before she was 21. In Joan’s mind a celestial censor always judged her severely for being neither a mysterious as Garbo nor as glamorous as Monroe.

“I’ve never seen anybody worry so much about how she looks,” marvels Beverly Archer, who worked with Van Ark in the series We’ve Got Each Other. “She practically has to have plastic surgery before she’ll let herself go on camera.”

Indeed, Van Ark is a bundle of contradictions of the sort that usually require psychiatric unraveling. Everything she does seems designed to bolster up her insecurities. This includes a comfortable, non-threatening, back-to-basics life style that gives Brownie points for good behavior and makes no concessions whatsoever to the Hollywood high life.

She and her husband, NBC newsman John Marshall (Who incidentally is also a runner), live in an unpretentious house in North Hollywood. (“I doubt if the place even has a Jacuzzi,” sniffs one of her colleagues.) They do not dine frequently at Ma Maison, Jimmy’s or any of the other fashionable watering holes. They do not fly to New York once a month to catch what’s chic to see on Broadway. If they travel anywhere, it’s more likely back to Boulder to give the high-school commencement address.

It is running and, in particular, the marathons (she has run 12 of them) that feed her vanity and keep her body in trim. They give her a kind of metaphoric fix-all for life. “Marriage can be painful,” she will tell you, “but, just like running, once you make the breakthrough, it can be gloriously, extravagantly worth it.”

The daughter of a Dutch public-relations man who, for reasons lost in history, named his oldest daughter after the saint, Joan was the prettiest girl in Boulder. Also the most gifted. At 10, she was writing plays for herself ad he little sister, Carol.

At 15, she had every body in town trying to date her. Among them was Jack Marsilio, the shy kid, who later called himself John Marshall.

“Jack was quite and vulnerable, not one of the smoothies,” she remembers. “He took me to Henrice’s in Denver for dinner and to see ‘Petrouchka’ afterward. The cowboys around the Twinburger couldn’t understand that.”

“She was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen,” he says. “I was shy but persistent. It was a funny kind of romance. I wanted to be a radio reporter. All she ever wanted was to act. it wouldn’t work out, everybody said.”

Van Ark went to Yale, Jack had already served an apprenticeship at a Denver radio station. Despite his dignified aspirations, his job as a rock jock had required him to wear a Lone Ranger mask and be known as “The Masked Marsilio.” For a serious young reporter, this proved nettlesome, and he ducked out as soon as he could. Periodically he checked in with Joan “Just to see how she was.”

After college, she began taking off like a shot. Director Mike Nichols himself sent for her to audition for the Elizabeth Ashley role in the national company of “Barefoot in the Park.” Very heady stuff. “They put me in the star’s dressing room to wait,” she recalls. “Oh God, I thought; Liz’s dressing room!

“Now, she may have been going to 10 psychiatrists, but for me she was the essence of the great lady, very together, very sure–a star. The aura of that dressing room did it. I never forgot it.”

Oddly enough, it was “Barefoot” that put the high-school lovers back on track. The now-unmasked Marsilio had set aside Denver radio and volunteered for the Armed Forces Radio Service in Germany. On night he got a telegram from Van Ark. She was coming to London to replace Marlo Thomas, who had torn a ligament, in “Barefoot.”

Marshall flew to London and suddenly there was another kind of crazy, romantic comedy being played out at the stage door. “The whole bit. Flowers, Candy, Hand-holding. Romantic idols. Then it was strictly weekends in Paris, two on the town,” says John.

They married early in 1968 in an Air Force chapel in Trier, Germany. They honeymooned by duplication Joan of Arc’s journey across France, a very Van-Ark-like thing to do. She is not entirely certain why she wanted to do this so much. “We just went,” she says, “to all the Joan places, starting with Domremy. Something drew me.”

Shortly thereafter she began to run.

She had to do something. “Jack was busy all day. I had a lot of energy,” she says. “I taught a little acting on the base. But it was not enough.”

Luckily, Marshall got a job with ABC in New York. Joan didn’t exactly devastate the town. But she had steady work. Her career slowed to a walk when they moved to Hollywood. But in 1971, when she returned to Broadway as the 16-yeah-old virgin in “The School for Wives,” her “innocence and simplicity” got her a Tony nomination–and Hollywood’s favor.

She still isn’t sure what she expected to find there. All she knew was that TV was in Hollywood, and she was fully prepared for whatever it might bring, including such forgettable series as Temperatures Rising and endless guest shots in everything from The Love Boat to Wonder Woman.

Knots Landing, a spin-off of Dallas, was an improvement of sorts. The part, while hardly taxing, was interesting, and some weeks were enlivened by a guest appearance by J.R. Ewing to tell her character, Valene, what an absolute plonk she was. moreover, Valene was “not one of those dumb little dames in the pantsuits. She may have been totally dependent on her husband, but she was committed and I love her.” insists Van Ark. “I see her as the living embodiment of Tammy Wynette singing ‘Stand by Your Man’.”

Nevertheless, running, not acting, became the dominant motif in her life. Soon Marshall took it up. He became a better runner than she was, 25 minutes faster in the Boston Marathon. But they do not run together. “It’s the perfect way to ruin a marriage,” says Van Ark, a reference to her independent bent.

Then there is daughter Vanessa, who has already appeared in Knots Landing. Van Ark had to figure out a way to have a “prefect” career, to work “Killing” hours and still have time enough for her 11-year-old. “She’s my pal, my buddy; I love her to death. But I’m not the Mother-of-the-year type,” she says. “No whipping up little batches of cookies in case she’s hungry when she gets home from school.”

Meantime, St. Joan occupies a more prominent place in her psyche than she likes to admit,. Last year Joan returned to Boulder to do Honegger’s oratorio, “Joan of Arc at the Stake.” This complex production, which she managed to rehearse and perform creditably with amateur talent in the course of a single week, approved a shattering experience both for her and for the audience. “I couldn’t speak afterward,” she says. “I had to leave to building to put myself back together. I get inexplicably emotional just thinking of Joan. . . . Have you thought what it would be like to burn at the stake?”

Mostly, however, she sidesteps anything that smacks of the saint’s spiritual influence. Call her feminist, call her philosopher, but just watch your references to her inner voices, even those that traditionally speak to gifted actresses. She is actually, she says, a Mary Poppins. “Like a Disney movie. I want everything to come up roses.”

As an athlete she is in constant demand. Last fall she and her husband, John; her sister, Carol Kuykendall; and her brothers, Kexter J. and Mark Clark Van Ark, took on the Van Pattens and the Devanes in a family special called “The Battle of Beverly Hills.” Everything was fine until the Van Arks blew the obstacle race and the Van Pattens breezed in, easy winners.

Joan scowls. “Van Arks don’t lose very gracefully,” she says evenly. “Van Arks like to win.” She doesn’t smile when she says it.